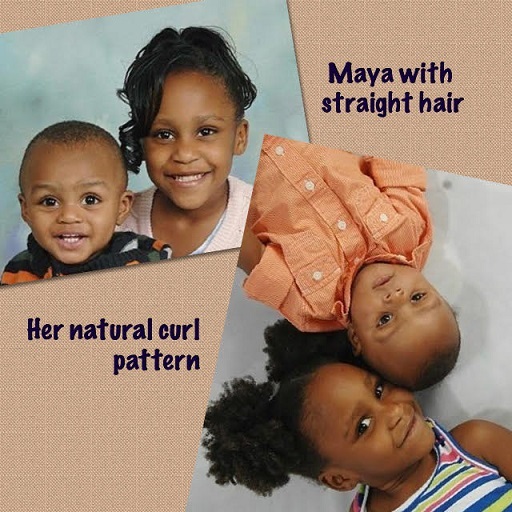

She immediately dropped her chin and pouted her bottom lip. She kept this expression the entire time, walking slowly through the gym with shame and embarrassment. I felt heartbroken. Later that day, without being asked, she apologized to her grandmother for visiting while her "hair wasn't done." When I think of the shame Maya felt that day, I think of journalist Stephanie Hinds and her similar connection to straight hair -- with straight hair, both feel safe and pretty.

Don't get me wrong, Maya thinks curly-haired Disney princesses like Merida are brave, but loves blonde, straight hair and holds it in high regard. Lately she's discovered older Disney characters, like Cinderella and Alice. At first glance she's enchanted by their gowns, but excitedly says in one breath, "Oooh Mommy she's beautiful and I want to be like her and have my hair look like hers."

Like me, more than 22 million millennials are raising the most culturally diverse generations to date, generation Z and generation Alpha. With so many similar, inaccurate representations of Black women in the media, teaching the Mayas of these new generations self-pride can be hard. I mean let's face it, no matter what burden Olivia Pope faces, she conquers it with hair permed and pressed to the Gods.

I've only had natural hair for the past four years, but don't be fooled -- I wore cornrows in a bun to my senior prom. I've never felt pressured to conform to anyone's image of beauty, I've never been a fan of being called pretty in comparison to other races, and I've never been a fan of being told I have features similar to those of other races. I compliment my White friends with straight hair, but not because I want to HAVE their hair. I appreciate their hair for what it is -- THEIR hair -- hoping they'll do the same for me: recognize my hair as a feature, not the definition of my character.

I can serve as an example for Maya, but it will take a woman from another Black generation to make her feel naturally beautiful.

Years before Maya was born, my three cousins and I attended a private screening of The Princess and the Frog, a movie featuring Tiana, Disney's first Black princess. After the screening, we attended a focus group with other Black millennial women to provide individual perspectives on beauty and overall feedback on the film.

I was asked countless questions, including "Does the media reinforce your idea of beauty?" and "Did you grow up uncomfortable with yourself because of the media?" But with each question I confidently replied, "I really don't care about the media, and because it doesn't represent me I don't think it cares about me either... we get along just fine. My grandmother defined what beauty is to me, encouraging me to be only the best version of ME." Much to the dismay of the facilitator, I didn't give her the answer she expected, one full of shame and struggle.

As a Black millennial I'm not alone in having the importance of self-love reinforced by my grandmother. In 2000 (when the last millennials were born), 6 million grandparents lived with a grandchild. To this day, Black members of generation Z and generation Alpha are still most likely to be cared for primarily by a grandparent when compared to other races. For Black children, ancestry and descended values are influential. Grandparents -- more specifically, grandmothers -- make Black children feel worthy of respect even in our rawest form.

Don't get me wrong, my grandmother battled with her own measurements of beauty, sometimes correlated to proximity to whiteness. But so did most Black women from the Silent Generation. Yet she never confronted me with those private issues. Instead, she drew from her personal experiences to, at 5 years old, give me "Edna's beauty manifesto":

Trying to look like anyone but you is not only dull for you but for everyone else too... so don't even bother. Focus on making your personality so boisterous that it literally radiates from your face. Make the world have no choice but to notice THAT first.

I'll admit: millennials are infamous for intentionally raising their children different than how they were raised. But with regards to this I've learned my lesson: I can't reinvent the wheel here.

As generation Z and generation Alpha become grandchildren of today's more active grandparents (generation X and Baby Boomers), it's still important they have a close bond with their grandmothers. Unfortunately some of today's grandmothers battle the same archaic "perm and press your hair!" thinking as my grandmother's generation. They should escape that and appreciate beauty techniques not typically accepted by Black women in the '80s and '90s. In other words, hair that's constantly permed AIN'T all that.

I need my mother to teach Maya what my grandmother taught me, because in today's world the noise not only comes from traditional media, but social media as well. The world's definition of beauty may fluctuate, but Maya should find comfort in the true definition of beauty never fluctuating from her grandmother. I want my mother to teach her contrary to what the media advertises, it's perfectly acceptable for Black hair to be worn in all states, styles and lengths. Teach her it's okay to want straight hair on a Monday and afro puffs on a Saturday, because it's her personality that matters.

So can I make a Black girl feel pretty? Nope. I can try, but my mother will succeed.

-- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

No comments:

Post a Comment